There have been many railroads serving Portland over the years, and in addition, the corporate politics of mergers and takeovers has been so complex that attaching a line to the name of only a single builder is nearly impossible. Labeling each with every railroad whose fingers touched it, however, is very cumbersome. location, creating the odd conundrum of the Twelfth Street Yard being located at 27th Street.

For the purpose of clarity, lines are identified by their owners in the year 1958. There are several reasons. First, 1958 was a recession year in the United States, accelerating the railways' "system rationalizations." In a sense, this year became a tipping point between the older, railroad oriented industrial pattern, and the new, decentralized, trucking-dependent economy.

Detail, Thirteenth and Lovejoy Streets, looking south. Photographer unknown, Public Works Administration, City of Portland, February 16, 1928. Portland Archives A2009-009.1205. Accession details pending.

These transportation companies numbered five (5) in 1958. The most important was arguably the Omaha-based Union Pacific (UP), which, beginning in 1889, slowly absorbed the Portland-based Oregon Railway & Navigation Company. The Southern Pacific (SP), headquartered in San Francisco, also operated switching lines on the east side of the city. Additionally, the UP and the SP were partners (along with the St. Paul, Minnesota based Northern Pacific) in owning the Northern Pacific Terminal Company (NPT), which held extensive lines on the city's northwest side, as well as operated Union Station. The fourth company of note was the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway (SP&S), which was controlled by two Minnesota-based railroads, the Great Northern (GN) and the Northern Pacific (NP), and which held extensive switching operations on both the west and east side of Portland on behalf of its parent companies. The final company was the Portland Traction Company (PTC), a descendent of the city's electric transit and power generation monopoly. The PTC was a bit player, with one district on the east side, and was controlled by San Francisco investors.

The term. Railroad terminology is evolutionary in nature. It is a mixture of technical communication written by managers and operations gurus, and an industrial slang composed on the fly by laborers in the field, searching for the clearest and most efficient way of doing their jobs.

The term "switching district" is no exception. It has numerous definitions. In some cases it is used synonymously with "switching zones", areas where more than one railroad has access to the same shippers via the same track through contractual agreements. In other cases it refers to areas with a high density of rail-served industry, loosely being synonymous with an industrial area. In other cases it refers specifically to industrial zones with enough traffic to warrant their own dedicated job (train).

For the purpose of this project, the working definition of a switching district is as follows:

A switching district comprises of a rail line constructed in the pre-Atomic age, located within a densely urbanized area, and often employing extensive street trackage. They are generally only a portion of a larger railroad company, and their primary purpose is to generate traffic from multiple industrial customers.

While this is an imperfect definition—as are all definitions—it unites most of the familiar aspects of urban railroading together.

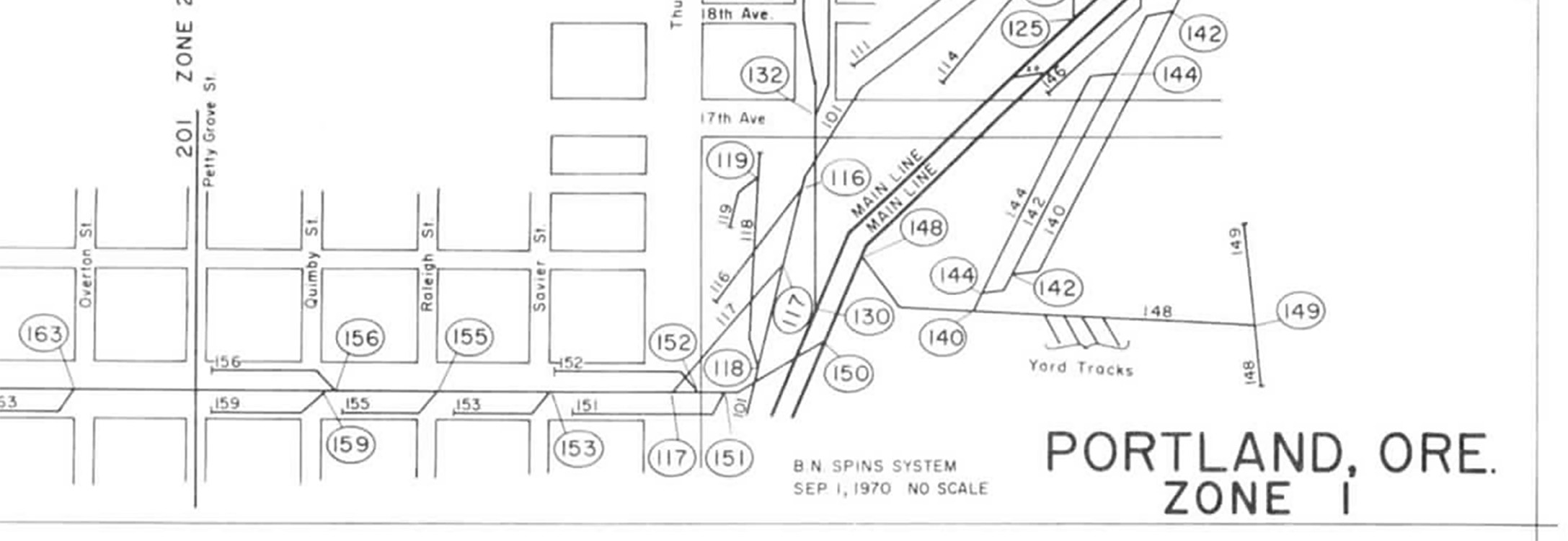

Urban switching districts forced railroad-dependent industrial uses into the dominant, pre-existing grid of American urbanism. Detail from Burlington Northern SPINS map for the Fifteenth Street district, 1970. Accession details pending.

District names. Note that at no point should the district names used here be confused for names used by railway workers in the 20th century. For example, it is unlikely that any Union Pacific employee ever referred to any of the trackage at the south end of the Albina yard as "the Albina Switching District." They would likely have referred to it casually by the actual street names being worked, such as River Street, or Loring Street, and so on.

This stated, I have endeavoured to use historically correct terms and names when possible, including calling avenues "streets" as they were when these lines would have been built, prior Portland's "great renaming" of the early 1930s. Another example is the Twelfth Street District, which was called "twelfth street" by its crews despite most of the track not being in that street at all, but on Pettygrove, 21st, and private right-of-way parallel to St. Helens Road. The name "twelfth street" comes from actual railroader use, because of the branch's eventual destination, rather than physical location, creating the odd conundrum of the Twelfth Street Yard being located at 27th Street.

Like many aspects of this project, names and terminology are ever-evolving, changing just as the city on the other side of the lens changes.

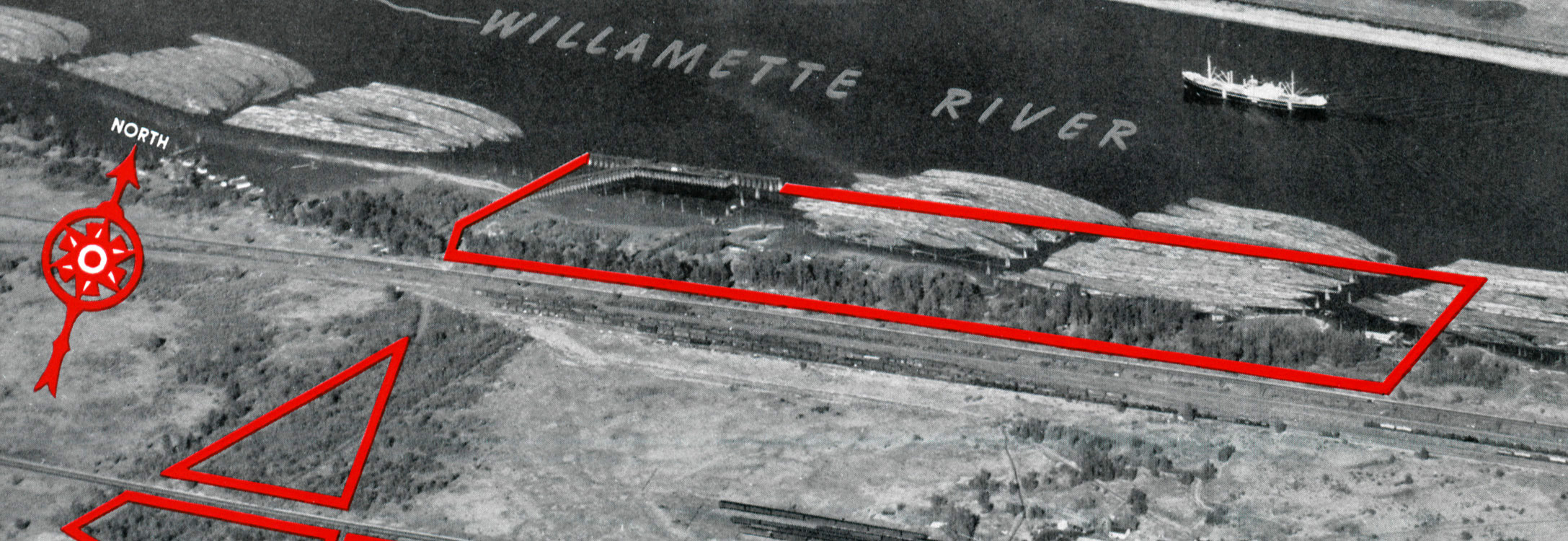

Waterfront development lots adjacent to the future Guilds Lake industrial park. These developments were attempts to augment and replace the switching district. Detail from Pacific Northwest Industrial Properties of the Union Pacific, circa 1950. Box 2(d), 6.

Inlusions and Exclusions. Eagle-eyed historians will note that some urban rail lines have been excluded, while others have seemingly been elevated as significant despite their modest size. For example, The Twelfth Street line—built as an interurban linking the city center with commuter suburbs—has been included as a district. The Southern Pacific's Jefferson Street line between Lake Oswego and downtown Portland, by contrast, has not been. Similarly, the Upsher Street line, only about five blocks long, is included alongside length districts like Fifteenth Street, once fourteen blocks long.

These decisions stem largely from the nature of this project as documenting what remained in 2008, fifty years after urban switching began a rapid decline. By that time, extensive development, road rebuilding, and transit construction had wiped away many lines. Although they do frequently have rail infrastructure, industrial parks have largely been excluded from the project. Some do overlap the switching district era—Larabee, Portland's first industrial park, was developed in the 1920s. Some, also, are located adjacent to switching districts—Guild's Lake was first conceived of as a series of traditional switching districts rather than an industrial park, and was located at the foot of the Twelfth Street district. Yet in these and other cases, industrial parks were developed far after the era of switching districts, and in fact represent an entirely separate logic of infrastructure and architecture. Where switching districts fit railroad infrastructure into the extant city, industrial parks were usually purpose-built on open land. They were typically designed to accommodate transportation, so that buildings fit the freight network, rather than the idealized urban grid. Finally, industrial parks were built to be served by both rail and trucks, a choice that was key to the decline of rail service in those parks. Thus, while industrial parks are part of the switching district story—as attempts by railroads to retain market share for shipments to and from urban industry—they figure at the edges of this project, rather than its center.

Albina had three short branches on River, Loring, and Railroad Streets, plus a switching lead to the Larabee Industrial Park on Larabee, now Interstate Avenue.

North is left.

Base image: n.d., Portland Archives A2004-002.6926.

Albina was originally a separate city, founded around the vast railroad yard and shops complex constructed here in the 1880s for the Northern Pacific Terminal Company.

The yard was transferred to a Union Pacific controlled subsidiary in 1889, and since that time Albina has been a UP railroad town.

Many residents of Albina worked for the railroad, and, thanks in part to the employment of Pullman porters, it became one of two historically African American neighborhoods in Portland.

Albina District

Union Pacific

PSDP Series "A"

Albina had several sections of industrial street trackage spread out across four streets: Larabee, Railroad, Loring, and River, with Railroad also being the mainline of the Union Pacific.

As each of these lines radiated out of the south end of the yard, they were operated concurrently and as-needed by yard crews, rather than meriting a dedicated switcher for each line.

For this reason, all four lines have been lumped together here as one.

Additionally, the Larabee spur was unique in several ways. First, it shared a short stretch of track with the narrow gauge (42") Portland Traction Mississippi Avenue line. This street trackage was located in the center of U.S. Highway 99 West, necessitating that service be restricted to night hours. Finally, the line ended at the Larabee Industrial Park, the city's first such development, constructed in the 1920s.

While most business in the Albina District has dried up, the Cal Portland (ex-Glacier Cement) aggregate dock alongside River Street keeps one line alive, while the Railroad Street line remains in service only as the southern approach to Albina Yard.

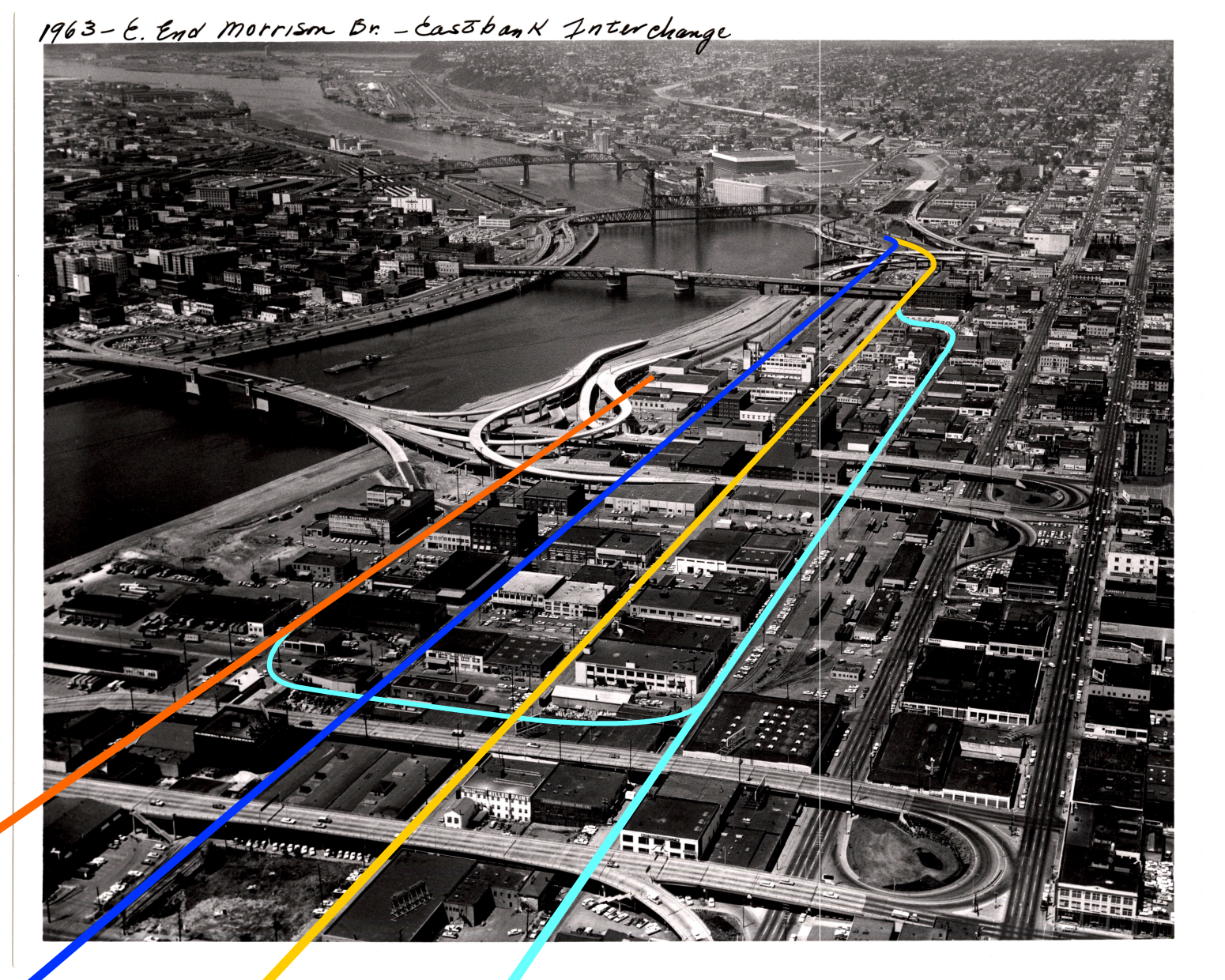

The Central Eastside had the densest districts.

L-R: Portland Traction on Water, Southern Pacific on First, Union Pacific on Second, Spokane, Portland & Seattle on Third.

Base image: 1963, Portland Archives A2005-001.479.

Like Albina, East Portland was founded as an independent city, and likewise was strongly tied to the railroad.

The Oregon Central drove its first spike in East Portland in 1868, and industry quickly began to develop around that line.

Following the success of the Oregon Central, which eventually became part of the Southern Pacific, several other railroads built into this area.

Much traffic in East Portland was perishable, giving the area the nickname "produce row."

Rail service in this area largely faded throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

While several produce distributors remain, they are primarily for the distribution of specialty food to Portland markets and restaurants, not for shipping Oregon's produce out-of-state, and they are entirely served by truck.

And although there has been a considerable amount of redevelopment in the last twenty years, much historic architecture survives, continuing to impart an industrial character.

Many Portlanders still refer to this area as "produce row," or by the slightly more cumbersome name given to it by regional planners, the "Central Eastside Industrial District" or "CEID."

Each of East Portland's four districts are described below, in the same L-R (West-east) order seen in the image above.

East Water Street

Portland Traction

PSDP Series "W"

This district protruded north from the Portland Traction Company's yards, which once sat beside the present Oregon Museum of Science and Industry.

Although the PTC was largely a transit operation, the company also sought a share of the city's lucrative industrial business, and the Water Street district allowed the company to serve East Portland's docks and waterfront.

Additionally, this district allowed the traction company to interchange with the Spokane, Portland & Seattle.

In 1958, the company's owners managed to shut its money-losing passenger service, and several years later the entire PTC was sold to the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific as a joint property, purely on the basis of its share of freight business.

The development of Interstate 5 along the river, and the decline of small-scale harbor-based businesses both undercut the viability of the Water Street district.

Most of this district went out of service in the late 20th century, and none remained in operation in 2008.

East First Street

Southern Pacific

PSDP Series "EF"

The first rail line in old East Portland, with rails laid in late 1868.

This was first the Oregon Central (later the Oregon & California), meant to connect Portland to the national rail network to the south.

Although older than all other railroads in the city, the O&C was the last of the potential trancontinentals to be completed, with the connection finished nearly twenty years later in 1887.

This mainline also became a prime switching district, at one point boasting four tracks, two for mainline service, and two outer tracks for car loading.

At the north end, the SP once had its freight terminals, handling less-than-carload business around the clock.

Although the mainline remains busy with freight trains for the Union Pacific and several daily Amtrak trains, no switching is still performed here, and except for one little-used spur at the north end, only the two main tracks remain.

One bit of trivia: although it occupies the right-of-way of First Street, and although First is signed with city street signs, the road here was never paved.

East Second Street

Union Pacific

PSDP Series "ES"

Alongside the SP, the Union Pacific was significantly responsible for developing East Portland, and its Second Street district served a variety of warehouses, factories, and produce distributors.

Soe of the largest and most impressive industrial structures in East Portland are along this line, including the old Sperry Flour Mills, and the former John Deere Plow manufacturing plant, a rare surviving example of a vertical manufacturing facility.

Although no service on this line remained in 2008, when this photo project began, most of the rail infrastructure was still intact and in relatively good shape.

The rails for this line did not disappear in a significant way until sewer projects necessitated the resurfacing of the roadways.

East Third Street

Spokane, Portland & Seattle Ry.

PSDP Series "ET"

The Spokane, Portland, & Seattle barely got into East Portland, being forced to lease its Third Street district from the Union Pacific.

The company wasted no time, using the district—which was wholly isolated from its lines, and reachable only via trackage rights—to attempt to secure a share of the east side's industrial traffic.

The SP&S built a freighthouse complex at Belmont, extending its reach via truck.

The district remained a small but important source of traffic for the company, in part bolstered by its interchange with the Portland Traction.

When the traction was sold to the UP and SP, the SP&S ceased receiving much interchange, reducing the value of its Third Street property.

Today, little remains of this district, in part because the large, flat freight yards made inexpensive buildable lots once the traffic declined.

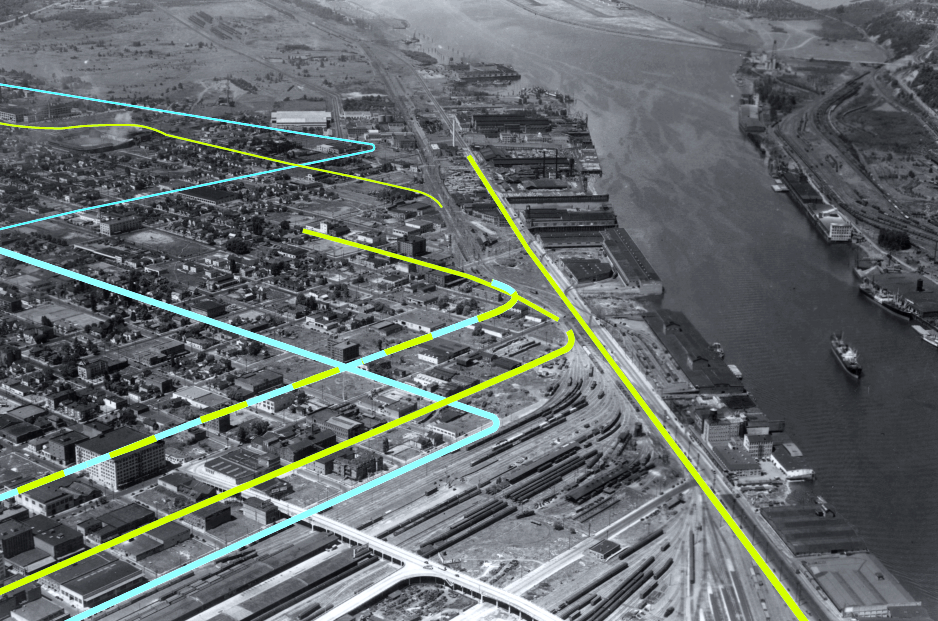

The west side's districts sprawled. The Twelfth Street line begins out of view to the north, then zig-zags across the city, reaching its namesake street at the bottom of this photo.

Its owner, the Spokane, Portland & Seattle, also shared trackage with the Northern Pacific Terminal on 15th.

The remainder of the lines in Northwest Portland belonged to the terminal company, and consisted of, from top to bottom, York, Front, Upsher, and 13th.

. Base image: c. 1935, Portland Archives A2005-005.1395.1

The west side of the city had the most number of switching districts, six in total, but also a wide variety of densities.

The 12th and 13th street lines terminated at Burnside, the very doorstep of downtown Portland, and served imposing multi-story warehouses and factories.

Others, such as the York Street line and the Upsher line, were built in relatively residential, even rural environments for the purpose of stimulating industrial development on unbuilt lands.

A strong relationship existed between these districts and the several rail yards and passenger terminals that cut up Northwest Portland.

The elimination of these districts was slow, but where it occurred, it had more to do with the pressures of Portland's residential and retail growth, than from industrial obsolescence.

The causes ranged from news freeways and new bridges, to the clean-up of polluted disused rail yards, to the demand for high-density residential towers.

While many old industrial buildings remain, most have been converted to condominiums.

This is especially true of the area adjacent to the old Spokane, Portland, and Seattle Hoyt Street yards, between 10th and 12th, which from the 1990s onwards were redeveloped into a new neighborhood called the "Pearl District."

The switching districts are presented below in a North-South order.

Twelfth Street

Spokane, Portland & Seattle Ry.

PSDP Series "TW"

This line began as an electric interurban, the United Railways, linking Portland to Linnton (opposite of St. Johns) and, via Cornelius Pass, the Tualatin Valley.

A latecomer to the city, the United did not do well as transit.

As an industrial line, it fared far better.

From its entry into the city on the edge of Guild's Lake, the United traversed 22nd, Pettygrove, and Twelfth, linking together more than thirty blocks of prime industrial sites.

Additionally, from Hoyt to Pettygrove, the line skirted the edge of the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway's Hoyt Street yard.

As owner of the United, the SP&S often used the Twelfth Street line to run transfers between Hoyt Street and its other yard at Willbridge.

Like all urban switching districts, Twelfth Street went into decline in the second half of the 20th century.

The southern end of the district remained used by the six-block Henry Weinhard's brewery complex at Burnside, right on the cusp of downtown.

In an attempt to improve its lot, the SP&S helped to develop the vast Guild's Lake industrial park along the top end of the district from the 1950s through the 1980s.

Some of this industrial park remains rail served, but it, too, has largely ceased shipping by rail.

The 1999 closure of the brewery ended service on the dense southern end of the district.

Only a short portion of the Twelfth Street line remained intact by 2008, a section along St. Helens Road.

In 2020, this, too, was taken out of service, eliminating the last activity on the Twelfth Street district.

Front Street

Northern Paciic Terminal Co.

PSDP Series "F"

Front Street was largely a dock serving district.

Its primary customers included a large lumber mill near the foot of 17th Street, and the Portland Public Docks, an early municipal freight terminal.

Additionally, this line served the massive Crown Flour complex at 9th Street, and the Albers Flour Mill further south, against the Broadway Bridge.

The Albers facility was redeveloped into a Class-A office building, but Crown Flour has proved less fortunate.

Several developers have attempted to repurpose the iconic Crown Flour building, and for a time the Portland police Bureau's mounted patrol kept its horses in a stable at this complex.

None of these proposals matured, however.

Between the 2008 and 2018 field work, large portions of Crown Flour was demolished, and the remainder awaits an uncertain fate.

York Street

Northern Paciic Terminal Co.

PSDP Series "Y"

This district was constructed primarily to connect to two industries.,

The first was the Montgomery Wards department store, which located its first Portland store on the edge of the city at 27th and Wilson.

The store, as built, had a set of tracks going straight into its basement for internal shipping and receiving.

The second was the Electric Steel Furnace Company (ESCO), a manufacturer of heavy machinery founded in 1913.

When constructed, the area around the district was either residential or unbuilt-upon.

Built in the 20th century, the line attracted developers of newer industries who needed larger lots.

The district was soon lined with spurs.

Ward's closed its store in the 1980s, although it had given up rail service long before that time.

It was ESCO that kept the line in business, making it important enough for the Oregon Department of Transportation to construct a bridge for York Street—complete with street trackage—in the 1970s.

The steel firm took regular deliveries of casting sand by rail, usually delivered in the wee hours of the morning by a Portland Terminal switching crew.

ESCO was ultimately York Street's first and last customer, closing the facility in 2016.

The plant has since been demolished, and thought the rail line remains intact, it is without a purpose.

Ward's, meanwhile, was converted into an office building, and still stands.

It remains the largest building by volume in the City of Portland.

Upsher Street

Northern Paciic Terminal Co.

PSDP Series "U"

Upsher is a short district, once serving a variety of small manufacturers, a feed plant at Vaughn Street, and a brewery.

Like York Street, Upsher was constructed in an area that had already been partially developed as a residential district.

A relatively short district, the bulk nature of its traffic—grain and chemicals—ensured that it remained in service long enough for its traces to survive, while nearby spurs on Roosevelt and Wilson disappeared long ago.

Although many boutique businesses now surround this line, infrastructure has yet to catch up.

Many street sections are poorly paved, and the switching lead remains obvious in many spots.

Fifteenth Street

Joint: Northern Paciic Terminal Co., Spokane, Portland & Seattle Ry.

PSDP Series "FI"

This district was built jointly by the Spokane, Portland & Seattle, and the Northern Pacific Terminal Company, after the former's entrance to Portland in the first decade of the 20th century.

Its construction represented the continuing expansion of the city's industrial economy, as developers began to build factories and warehouses in areas that had once been fashionable residential districts.

Fifteenth was once unique for its monotonous symmetry.

Laid out all at once and for the express purpose of industrial development, Fifteenth had "three-way" switches at almost every block, ensuring a regular, dense amount of spurs.

Major customers included the Meier & Frank Department Store, headquartered in Portland, who built its regional warehouse along the district.

The development of Interstate 405 and the approaches to the Fremont Bridge eventually wiped out all structures—and, consequently, all railroad customers—on the west side of the road during the 1970s.

Although long out of service, much of the rail infrastructure on 15th remained in place even in the second decade of the 21t century.

Thirteenth Street

Northern Paciic Terminal Co.

PSDP Series "TH"

Thirteenth was one of the westside's denser districts, with many multi-story industrial buildings in handsome brick romanesque styles.

Probably this expensive and solid construction is precisely what doomed the line, as it made adaptation to new manufacturing uses more difficult.

Thirteenth is unusual in that it remained in service as late as 2001, its last customer being Bridgeport Brewing between Marshall and Northrup.

When the Portland Streetcar system was constructed in 2000, the new transit line was required to install an at-grade crossing with the Thirteenth Street District, in order to allow Bridgeport to continue receiving carloads of grain.

Bridgeport eventually moved over to fully truck service, however, and the crossing was removed a few years later.

Almost all rail infrastructure on 13th has been removed, when the city installed a new "curbless street" design that reversed the traditional pavement camber towards a center depression.

The street is now primarily a retail and entertainment street, with boutique businesses located in the former warehouses and factories.

The architecture of the area, however, remains well preserved, evidence of the street's industrial past.

Project Note. Some of these districts were originally photographed during the fieldwork of 2007-2009, but have since been withdrawn. This includes PSDP series "L" (Larrabee: Union Pacific), series "G" (Guild's Lake: Spokane, Portland & Seattle Ry.), and series "M" (Macadam Street: Southern Pacific, Spokane, Portland & Seattle Ry.).